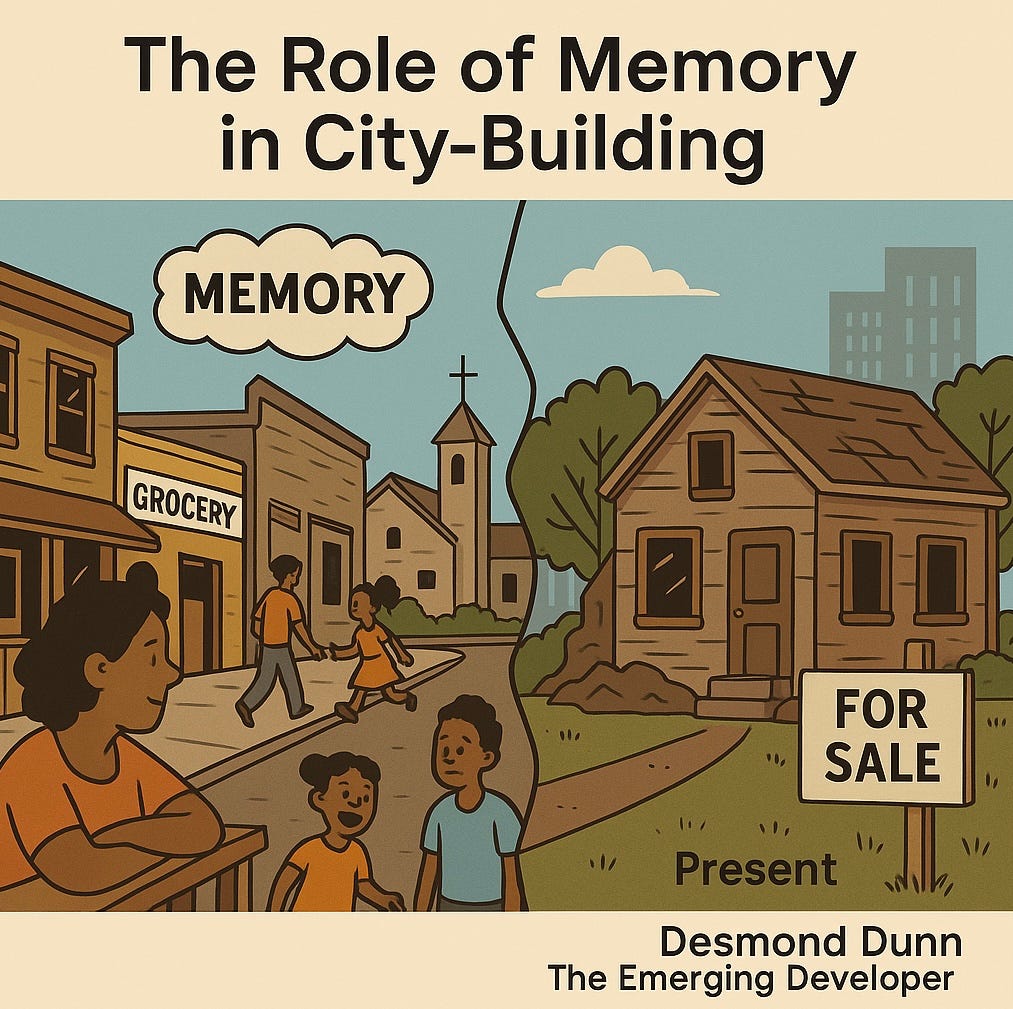

The Role of Memory in City-Building

Cities are more than roads, buildings, and zoning maps. They are living records.

Every street corner holds stories, some celebrated, some silenced. Memory is a kind of infrastructure too. It shapes how we understand place, how we measure belonging, and how we decide what to build next.

But what happens when memory is erased?

In Raleigh, that’s not a hypothetical question. It’s history.

Erased Neighborhoods, Erased Futures

Take Smoky Hollow, once a thriving working-class and Black neighborhood. Or South Park, a hub of commerce, culture, and community. Families built lives there. Kids walked to schools. Neighbors shared gardens, porches, and corner stores. These places functioned as what we now call “15-minute cities,” where daily needs were within walking distance and community ties held everything together.

But those neighborhoods were labeled “blighted.” Urban renewal and highway projects in the mid-20th century bulldozed homes and businesses to make way for government buildings, new infrastructure, or empty promises of redevelopment. As Carmen Wimberley Cauthen documents in Historic Black Neighborhoods of Raleigh, what was destroyed was not just physical space but social and economic ecosystems.

Land was seized through eminent domain. Families were displaced. Businesses closed. And with them, the chance to pass down wealth, property, and community memory.

This wasn’t natural decline. It was deliberate engineered removal.

Why Memory Matters for Today’s Cities

When we talk about affordable housing or urban design today, it’s easy to focus on the “new”: new units, new zoning, new projects. But without memory, we risk repeating the same mistakes.

Memory does three things for city-building:

It holds us accountable. Remembering how neighborhoods were dismantled makes it harder to hide behind the idea that displacement is inevitable. It shows us that erasure was a choice, and that repair can be a choice too.

It preserves belonging. Communities are more than parcels on a map. They’re webs of relationships. Memory keeps those webs alive, even when the physical structures are gone.

It provides blueprints. Many of the principles planners now celebrate, walkability, mixed-use, density, social cohesion, already existed in these erased neighborhoods. The past can guide the future.

Designing With Memory in Mind

So what does it mean to build with memory at the center?

Preserve and interpret. Historic preservation can’t just be plaques on buildings. It has to be active, storytelling through murals, community centers, oral histories, and spaces that make memory visible and accessible.

Honor legacy residents. Policy has to go beyond engagement sessions. It means embedding protections like first-right-to-purchase programs, tax relief, and affordable ownership models so long-time residents can remain part of the story.

Rebuild ecosystems, not just units. Affordable housing should be tied to schools, small businesses, cultural spaces, and transit, the things that made historic neighborhoods resilient in the first place.

Plan with history in the room. Books like Historic Black Neighborhoods of Raleigh should sit next to zoning codes in every planning office. Because design without memory is just repetition with new paint.

Memory as Justice

To me, memory is more than a look backward. It’s a demand for justice.

When we rebuild neighborhoods today, we are working on land that carries history. Ignoring that history means ignoring the harm that was done, and missing the opportunity to repair it.

Cities that choose to build with memory have the chance to do more than add housing units. They can restore belonging. They can create continuity. They can honor the people whose sacrifices built the places we now call home.

Because memory is not nostalgia. It’s infrastructure. It’s what makes a city more than a collection of parcels. It’s what makes it human.

Moving Forward

The role of memory in city-building is simple but powerful: never forget what was taken, and never stop building toward what was possible.

In Raleigh, that means honoring the stories of Smoky Hollow, South Park, and East Raleigh as we imagine new projects. It means designing not just for compliance, but for continuity. It means asking: if this land has already held a thriving community once before, how can we make it whole again?

Because if erasure was intentional, so too must be repair.

What’s one erased neighborhood in your city whose memory we should carry forward into the future?